Metaontology. Toward a prehuman thinking

Chapter 1 - Why metaontology?

2020-02-05

Wonder

διὰ γὰρ τὸ θαυμάζειν οἱ ἄνθρωποι καὶ νῦν καὶ τὸ πρῶτον ἤρξαντο φιλοσοφεῖν, ἐξ ἀρχῆς μὲν τὰ πρόχειρα τῶν ἀτόπων θαυμάσαντες, εἶτα κατὰ μικρὸν οὕτω προϊόντες καὶ περὶ τῶν μειζόνων διαπορήσαντες, οἷον περί τε τῶν τῆς σελήνης παθημάτων καὶ τῶν περὶ τὸν ἥλιον καὶ ἄστρα καὶ περὶ τῆς τοῦ παντὸς γενέσεως. (Aristotle 1989, 1, 2982b 10, See annotation)1 μάλα γὰρ φιλοσόφου τοῦτο τὸ πάθος, τὸ θαυμάζειν: οὐ γὰρ ἄλλη ἀρχὴ φιλοσοφίας ἢ αὕτη, καὶ ἔοικεν ὁ τὴν Ἶριν Θαύμαντος ἔκγονον φήσας οὐ κακῶς γενεαλογεῖν. (Plato 1902, Theaet. 155d See annotation)2 Wonders. The world is full of wonders. Wonder is something captivating, charming and incomprehensible. Wonder thus calls for explanations. It calls for reflection, for thinking, for philosophy and, more generally, for mediation.

Θαύμας δ᾽ Ὠκεανοῖο βαθυρρείταο θύγατρα ἠγάγετ᾽ Ἠλέκτρην: ἣ δ᾽ ὠκεῖαν τέκεν Ἶριν. (Hesiod and Evelyn-White 1914, Th. 265. See annotation)3 In Greek mythology, Thaumas (wonder) is the son of Pontus (the sea) and Gaia (the Earth): the world—earth and sea—generates wonder. Thaumas is also the father of Iris, who is messenger of the gods and the goddess of the rainbow: during the war between gods and titans—the Titanomachy—she enables mediation between the earth and the Olympus—a mediation for which the rainbow serves as a metaphor. Iris allegorizes mediation.

Si el pensamiento nació de la admiratión solamente, según nos dicen textos venerables, no se explica con facilidad que fuera tan prontamente a plasmarse en forma de filosofía sistemática. […] Porque la admiratión que nos produce la generosa existencia de la vida en torno nuestro no permite tan rápido desprendimiento de las múltiples maravillas que la suscitan. (Zambrano 1939, Chapter 1.)4 This mediation between an immanent world and transcendence can be understood as a form of thinking. To think is to depart from the world and to connect it to something else, something external, and then to return to the world: exactly as a rainbow, exactly as Iris.

Here is a series of intertwined notions: world, wonder, mediation, thinking and, finally, philosophy which is a particular form of thinking instigated by wonder. This collection of words will be the starting point of this text.

La poesía perseguía, entre tanto, la multiplicidad desdeñada,la menospeciada heterogeneitad. […] Con esto tocamos el punto más delicado quiza de todos: el que proviene de la consideratión “unitad-heterogenitad”. […] El ser había sido definido con unitad ante todo […]. Las apariencias se destruyen unas a otras[…]. Quien tiene, pues, la unitad lo tiene todo. (Zambrano 1939, Chapter 1.)5 A text that questions this series of notions is necessarily philosophical, it is thus crucial to begin to identify philosophy as a particular form of thinking that comprises many particularities. So here is an initial, albeit tentative, definition of philosophy: philosophy is a desire, produced by wonder, to reduce the multiplicity of the world to a unity. La filosofía es un éxtasis fracasado por un desgarramiento. (Zambrano 1939, Chapter 1.)6 Philosophy is the bastard daughter of Thaumas. Thaumas is necessary multiple: wonder is a condition derived from the multiplicity of the world and from everything that the world contains. Philosophy is also a prodigal child who, struggling against her father, attempts to destroy this multiplicity and bring it back to a unity. To bring it back. This is the problem. From a philosophical standpoint, it is impossible to even think that multiplicity could precede unity. Unity comes first; the question can only be how to bring it back.

Starting from this fundamental problem, this first chapter will explain the necessity of metaontology as an approach to such questions. It will try to answer two interrelated questions. First: why is metaontology necessary? And furthermore: why it is necessary today? This indicates that metaontology requires two perspectives: from a timeless and ahistorical point of view, and from a contemporary, place and time specific and historical view. In fact, metaontology tries to answer some very general questions that have been at the centre of philosophical enquiry since its beginnings: in this sense, metaontology purports to be a possible answer to the main philosophical questions. It is consequently necessary to explain why these questions remain urgent. At the same time, however, metaontology emerges in a particular historical moment, in a particular society, within a series of very specific conditions: it is thus necessary to explain why metaontology emerges today, how it can be useful in the very moment of its emergence and how it can be related to the broader intellectual landscape that it surrounds.

Ahistorical reasons

Warum ist überhaupt Seiendes und nicht vielmehr Nichts? Das ist die Frage. Vermutlich ist dies keine beliebige Frage. »War- um ist überhaupt Seiendes und nicht vielmehr Nichts?« — das ist offensichtlich die erste aller Fragen. Die erste, freilich nicht in der Ordnung der zeitlichen Aufeinanderfolge der Fragen. Der einzelne Mensch sowohl wie die Völker fragen auf ihrem geschichtlichen Gang durch die Zeit vieles. Sie erkunden und durchsuchen und prüfen Vielerlei, bevor sie auf die Frage sto- ßen: »Warum ist überhaupt Seiendes und nicht vielmehr Nichts?« Viele stoßen überhaupt nie auf diese Frage, wenn das heißen soll, nicht nur den Fragesatz als ausgesagten hören und lesen, sondern: die Frage fragen, d. h. sie zustandbringen, sie stellen, sich in den Zustand dieses Fragens nötigen.

Und dennoch! Jeder wird einmal, vielleicht sogar dann und wann, von der verborgenen Macht dieser Frage gestreift, ohne recht zu fassen, was ihm geschieht. In einer großen Verzweif- lung z. B., wo alles Gewicht aus den Dingen schwinden will und jeder Sinn sich verdunkelt, steht die Frage auf. (Heidegger 1935, 3. See annotation)7 The world generates wonder. The world is a problem to solve. Metaontology emerges from this problematic dimension. And yet it is necessary to describe what poses the problem, to identify the obstacle. What is the problem that produces the need for metaontology and what exactly is the object of the wonder? Here is an initial and very broad formulation of wonder: why are there things?

This apparently banal question can be broken down into several questions. First of all, why is there something? This is the fundamental metaphysical question, that is: Why are there beings at all, instead of nothing? Then there is a second problem: why are there things, namely several things?; or better: how is it possible that there are things rather than one thing? This is the fundamental problem at the heart of metaontological enquiry, in its ahistorical formulation: how to think the relationship between unity and multiplicity? While these two questions are probably not entirely ahistorical—as this text will show by presenting the historical reasons why these questions seem so urgent today—, they are insofar as they intersect with the totality of the Western philosophical tradition (to briefly summarize, from Parmenides to Heidegger and beyond). This chapter will offer an analysis of these two sempiternal questions in order to prepare the intellectual terrain for this work on metaontology.

Being and thinking

À nouveau j’étais unique et j’étais exigée; il fallait mon regard pour que le rouge du hêtre rencontrât le bleu du cèdre et l’argent des peupliers. Lorsque je m’en allais le paysage se défaisait, il n’existait plus pour personne: il n’existait plus du tout. Mémoire d’une jeune fille rangée 165-166 Here is the sea.

The wonder appears and it manifests itself into a series of interconnected questions:

- First of all: is the sea here? Is there anything which can assure the validity of the above sentence, “here is the sea”? How can one be sure that the sea is actually here or there? What are the rules to follow to make sure that this sentence has an objective, universal value? 31. Nos raisonnemens sont fondés sur deux grands principes, celui de la contradiction, en vertu duquel nous jugeons faux ce qui en enveloppe, et vrai ce qui est oppose ou contradictoire au faux.

32. Et celui de la raison suffisante, en vertu duquel nous considérons qu’aucun fait ne sauroit se trouver vrai ou existant, aucune énonciation véritable, sans qu’il y ait une raison suffisante pourquoi il en soit ainsi et non pas autrement, quoique ces raisons le plus souvent ne puissent point nous être connues. https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Monadologie_(%C3%89dition_Gerhardt,_1885)(Leibniz 2008 see annotation) - Second question: if one admits that the sea is here, then why is it here? Is there any reason, any principle, any fact that determines that the sea is here? Why, for example, is the sea here and why does it not take the form of a lake, or a dog, or a unicorn? What is the force that makes some things into being and others into nothingness?

- Third question: what does “here” mean? “Here” is an adverb which only has meaning when considered in relation to something else: the sea is here for a dog, a fly, a human being—the reader of this text?—, a rock. The sea can only be “here” when considered in relation to another element. Which element? And what is the nature of their relationship?

- Finally: can one simply say that the sea is without specifying that it is here? Or, in other terms, is the sea still here if nothing and nobody is in front of it in order to account for the fact that it is here?

A like reasoning will account for the idea of external existence. We may observe, that it is universally allowed by philosophers, and is besides pretty obvious of itself, that nothing is ever really present with the mind but its perceptions or impressions and ideas, and that external objects become known to us only by those perceptions they occasion. To hate, to love, to think, to feel, to see; all this is nothing but to perceive.i

Now since nothing is ever present to the mind but perceptions, and since all ideas are derived from something antecedently present to the mind; it follows, that it is impossible for us so much as to conceive or form an idea of any thing specifically different from ideas and impressions. Let us fix our attention out of ourselves as much as possible: Let us chase our imagination to the heavens, or to the utmost limits of the universe; we never really advance a step beyond ourselves, nor can conceive any kind of existence, but those perceptions, which have appeared in that narrow compass. This is the universe of the imagination, nor have we any idea but what is there produced. https://web.archive.org/web/20060824184722/http://etext.library.adelaide.edu.au/h/hume/david/h92t/chapter13.html These questions are inseparable from one another, as the answer for each feeds into another’s answer.

Finally, in order to round off this brief exposition of the post- critical philosopheme, we must emphasize that the correlation between thought and being is not reducible to the correlation between subject and object. In other words, the fact that correlation dominates contemporary philosophy in no way implies the dominance of philosophies of representation. It is possible to criticize the latter in the name of a more originary correlation between thought and being. And in fact, the critiques of representation have not signalled a break with correlation, i.e. a simple return to dogmatism. On this point, let us confine ourselves to giving one example: that of Heidegger. On the one hand, for Heidegger, it is certainly a case of pinpointing the occlusion of being or presence inherent in every metaphysical conception of representation and the privileging of the present at-hand entity considered as object. Yet on the other hand, to think such an occlusion at the heart of the unconcealment of the entity requires, for Heidegger, that one take into account the co-propriation (Zusammengehb’rigkeit) of man and being, which he calls Ereignis 9 . Thus, the notion of Ereignis, which is central in the later Heidegger, remains faithful to the correlationist exigency inherited from Kant and continued in Husserlian phenomenology, for the ‘co-propriation’ which constitutes Ereignis means that neither being nor man can be posited as subsisting ‘in-themselves’, and subsequently entering into relation - on the contrary, both terms of the appropriation are originarily constituted through their reciprocal relation: ‘The appropriation appropriates man and Being to their essential togetherness.’(Meillassoux 2009, 17) In order to understand the following analysis, it is important to make explicit the meaning this text gives to two key notions: world and Being. For the purpose of this first chapter, the concept of world will be tentatively defined as follows: the world is everything which is. As for Being, the term may be defined as that by which what is is. Given that this definition poses many problems, it will be questioned and reframed over the course of this text, in particular in chapter 5. For now, this text will obliterate the difference between world and Being and temporarily dismiss the ontological difference between Being and that which is. The world and Being will, for now, be considered synonyms. This changes nothing regarding the relationship between thinking and Being addressed here.

So: the sea is here. It is big, vast. It is blue. It is, maybe, beautiful, sublime. It is

the connected body of salty water that covers over 70 percent of the Earth’s surface. It moderates the Earth’s climate and has important roles in the water cycle, carbon cycle, and nitrogen cycle. (“Sea” 2018).

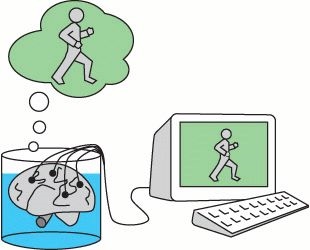

It seems that the only way to affirm that the sea is here and to respond to the four above questions would be to have something or someone before it. One can say that the sea is here because it is before something. This can be described as a very formal definition of thinking: the connection between the world—in this example, the sea—and something else—whatever this “something” is. In this sense, thinking is understood here as the formal word to describe any kind of relationship between a thing and something else: perception, imagination, memory…

The sea is here because there is something that relates to it; Being is always related to a form of thinking.

But what happens when there is nothing there to witness the sea? Is it still there? Is it still big, vast, blue, beautiful, sublime? Is it still “the connected body of salty water that covers over 70 percent of the Earth’s surface”?

In fact, nobody knows, for the very reason that in order to “know” it, someone, or something, must “think” it. Apparently, nobody can know anything about what the world is, although this may seem absurd. In order to know whether the sea is there, it is necessary to have someone in front of it: the sea must be, once again, “before someone” or “before something”.

This problem is one of the most common obsessions of Western thought. It is an obsession — and a paradox — that has haunted philosophical history since its beginnings; it constitutes a primary preoccupation for countless philosophical texts.

9. Primary Qualities of Bodies. Concerning these qualities, we, I think, observe these primary ones in bodies that produce simple ideas in us, viz. SOLIDITY, EXTENSION, MOTION or REST, NUMBER or FIGURE. These, which I call ORIGINAL or PRIMARY qualities of body, are wholly inseperable from it […] 14. They depend on the primary Qualities. What I have said concerning colours and smells may be understood also of tastes and sounds, and other the like sensible qualities; which, whatever reality we by mistake attribute to them, are in truth nothing in the objects themselves, but powers to produce various sensations in us; and depend on those primary qualities, viz. bulk, figure, texture, and motion of parts and therefore I call them SECONDARY QUALITIES. (Locke 2004, Book II, 9, 14, see annotation) A possible solution to this problem is to distinguish between things in themselves and things for someone. Each thing would be something in itself, which means regardless of whether it has any relationship to something else. The world is —or Being is— regardless of its relationship to thinking. The same thing can also have some other qualities which depend on what relationships this thing has with something else. For example: how it is perceived and by whom or what. These qualities define what a thing is for someone or something. In this case, the world, Being, is, but only in relation to some form of thinking.

To return to the sea: it is something in itself; it has, probably, some qualities regardless of the relationships it can have with something in front of it. If nobody is before it, the sea in itself remains the same. On the other hand, some properties depend on the relationship the sea has with some particular form of thinking: for example, a fly, compared to a human will perceive that it is a different colour. Therefore, for instance, the colour of the sea is blue only because a human being is perceiving it as blue; once there is no longer a human being in front of it, the sea is no longer blue.

Whereas I say, that things as objects of our senses existing outside us are given, but we know nothing of what they may be in themselves, knowing only their appearances, i.e., the representations which they cause in us by affecting our senses. Consequently I grant by all means that there are bodies without us, that is, things which, though quite unknown to us as to what they are in themselves, we yet know by the representations which their influence on our sensibility procures us, and which we call bodies, a term signifying merely the appearance of the thing which is unknown to us, but not therefore less actual. (Emmanuel Kant 1902, Part I Remark II, See annotation)8 It can, however, only be stated that the sea “probably” has some qualities in itself. It is impossible to respond to the first question without imagining someone or something “before it”. This means, in other words, that it is impossible to state that “the sea is”, without adding the adverb “here” (question 3) which implies a relationship to something in front of it. And finally, this means that the only reason that the sea is here (question 2) is that someone or something is before it and looking at it, or imagining it, or remembering it, or more generally thinking it—according to the very formal and broad definition of thinking proposed above—, and therefore that there is no sea if nothing and nobody is in front of it (question 4). In other words: there is no world without thinking—and, more generally, there is no Being without thinking.

Any distinction between a thing in itself and a thing for someone or something cannot be proven and is thus dogmatic. Indeed, how can one know the qualities that would be specific to the object—what an object is in itself, independently of something or someone thinking it—if one can only refer to it while one thinks it?

Es ist hiemit eben so, als mit den ersten Gedanken des Copernicus bewandt, der, nachdem es mit der Erklärung der Himmelsbewegungen nicht gut fort wollte, wenn er annahm, das ganze Sternheer drehe sich um den Zuschauer, versuchte, ob es nicht besser gelingen möchte, wenn er den Zuschauer sich drehen und dagegen die Sterne in Ruhe ließ. In der Metaphysik kann man nun, was die Anschauung der Gegenstände betrifft, es auf ähnliche Weise versuchen. Wenn die Anschauung sich nach der Beschaffenheit der Gegenstände richten müßte, so sehe ich nicht ein, wie man a priori von ihr etwas wissen könne; richtet sich aber der Gegenstand (als Object der Sinne) nach der Beschaffenheit unseres Anschauungsvermögens, so kann ich mir diese Möglichkeit ganz wohl vorstellen. https://korpora.zim.uni-duisburg-essen.de/Kant/aa03/012.html9 Once again: the only way to assure the validity of the sentence “the sea is here” is for someone or something to witness or to bear witness to it.

But what is this “something” that has a relationship with the world? A first answer, which seems quite obvious—and which will, from chapter 2, be interrogated—, is that the only possible thing one can imagine “before” the world in order to think it is a human being. This answer is strongly supported by the particular form of philosophical discourse. Philosophy is often interpreted as the discourse of a particular human being, the one who is writing or saying a philosophical statement. This human being refers to oneself as “I”, and to other human beings as “us”. This text avoids such formulations. The enunciator here is, always, the text, as this alternative enables a more apt description of the real, material situation of this discourse, which is in reality a textual inscription. The analysis of this particular situation is an integral interest of this text. For now, suffice to say that identifying the “something” which is “in front” of the world with a human being is probably an assumption determining the problems described in this first chapter. This is one reason necessitating metaontology. Metaontology is—among other things—an approach focusing on the very material forms of the production of text; it questions the idea that the origin of the philosophical discourse is necessarily a human being.

In fact, the idea that “Being is” only if something relates to it and that this something is necessarily a human being, leads to a strange paradox: on the one hand, there is a world that exists independently of human beings, but which, for that very reason, is totally inaccessible to them—and so they cannot affirm anything about its properties, not even that it exists; on the other hand, there is a world that exists only because human beings have access to it, but its existence is determined by their relationship with it. The former statement implies that there is a world without access to the world, whereas the latter affirms that there is an access to the world without a world. This is the paradox of access.

Albeit somewhat caricatured, these two philosophical positions can be defined as “dogmatic realism” and “correlationism”, respectively.

By ‘correlation’ we mean the idea according to which we only ever have access to the correlation between thinking and being, and never to either term considered apart from the other. We will henceforth call correlationism any current of thought which maintains the unsurpassable character of the correlation so defined. (Meillassoux 2009, 13.)10

Dogmatic realism requires dogmatism in order to be realist: to affirm that there is a reality, it must disregard all experience and base its affirmation of reality on an a priori which is neither demonstrable, nor rational. The world, says the dogmatic realist, exists independently of human beings. There is no way to prove this, and their assertion is therefore dogmatic. Correlationism consists in avoiding the realist’s dogmatic naivety by asserting that human beings can only talk about what they can access.

If one insists that metaphysical realism is incoherent (because we cannot even discuss realism outside of language or outside our context of practices), then one is openly stating that philosophy can be concerned only with our access to things. And this is idealism pure and simple, whether “transcendental” or not. (Harman 2002, 123)

But in doing, so correlationism risks falling into a radical constructivist logic whereby the world is no more than a product of the human mind. If the world is only what human beings think or perceive, they risk being unable to prevent everyone from seeing the world that they would like and to build reality as they see fit. How is it possible to avoid historical negationism, for example? Is it possible to refer to a sense of reality as a means of countering fake news or conspiracy theories?

Je supposerai donc, non pas que Dieu, qui est très bon, et qui est la souveraine source de vérité, mais qu’un certain mauvais génie, non moins rusé et trompeur que puissant, a employé toute son industrie à me tromper ; je penserai que le ciel, l’air, la terre, les couleurs, les figures, les sons, et toutes les choses extérieures, ne sont rien que des illusions et rêveries dont il s’est servi pour tendre des piéges à ma crédulité ; je me considérerai moi-même comme n’ayant point de mains, point d’yeux, point de chair, point de sang ; comme n’ayant aucun sens, mais croyant faussement avoir toutes ces choses ; je demeurerai obstinément attaché à cette pensée ; et si, par ce moyen, il n’est pas en mon pouvoir de parvenir à la connoissance d’aucune vérité, à tout le moins il est en ma puissance de suspendre mon jugement : c’est pourquoi je prendrai garde soigneusement de ne recevoir en ma croyance aucune fausseté, et préparerai si bien mon esprit à toutes les ruses de ce grand trompeur, que, pour puissant et rusé qu’il soit, il ne me pourra jamais rien imposer. https://fr.m.wikisource.org/wiki/M%C3%A9ditations_m%C3%A9taphysiques/M%C3%A9ditation_premi%C3%A8re The problem of a radical form of correlationism is that it allows for any form of doubt about the world. The only answer that a correlationist can give to question 2 is that “things are there” only because somebody thinks them. This implies that nothing guarantees that the world is only the hallucination of a particular human being. This fear is a topos present in philosophy as well as literature, cinema and the arts. This topos seems to be renewed at the time of digital technologies—an issue that will be addressed later in this text.

Another philosophical problem tied to correlationism is that some statements regarded as scientifically valid appear to be void of meaning if we do not accept the existence of the world beyond our perception of it.

Let us proceed then from this simple observation: today’s science formulates a certain number of ancestral statements bearing upon the age of the universe, the formation of stars, or the accretion of the earth. Obviously it is not part of our remit to appraise the reliability of the techniques employed in order to formulate such statements. What we are interested in, howevei, is understanding under what conditions these statements are meaningful. More precisely, we ask: how is correlationism liable to interpret these ancestral statements? (Meillassoux 2009, 21)11

This is particularly true for scientific statements concerning a time anterior—sometimes very anterior—to the origin of the human species. What would be the meaning of statements concerning geological eras, for example, when at that time there could be no access to the world simply because there were no human beings? According to a correlationist approach, statements that relate to eras prior to mankind have meaning only after a “retrojection of the past on the basis of the present”: this past exists only now, for human beings today. And yet, this does not take into account the fact that this kind of scientific statement refers to a real past entirely independent of human access.

Ainsi, à cause que nos sens nous trompent quelquefois, je voulus supposer qu’il n’y avoit aucune chose qui fût telle qu’ils nous la font imaginer ; et parcequ’il y a des hommes qui se méprennent en raisonnant, même touchant les plus simples matières de géométrie, et y font des paralogismes, jugeant que j’étois sujet à faillir autant qu’aucun autre, je rejetai comme fausses toutes les raisons que j’avois prises auparavant pour démonstrations ; et enfin, considérant que toutes les mêmes pensées que nous avons étant éveillés nous peuvent aussi venir quand nous dormons, sans qu’il y en ait aucune pour lors qui soit vraie, je me résolus de feindre que toutes les choses qui m’étoient jamais entrées en l’esprit n’étoient non plus vraies que les illusions de mes songes. Mais aussitôt après je pris garde que, pendant que je voulois ainsi penser que tout étoit faux, il falloit nécessairement que moi qui le pensois fusse quelque chose ; et remarquant que cette vérité, je pense, donc je suis, étoit si ferme et si assurée, que toutes les plus extravagantes suppositions des sceptiques n’étoient pas capables de l’ébranler, je jugeai que je pouvois la recevoir sans scrupule pour le premier principe de la philosophie que je cherchois. https://fr.m.wikisource.org/wiki/Discours_de_la_m%C3%A9thode_(%C3%A9d._Cousin)/Quatri%C3%A8me_partie

Both dogmatic realism and correlationism therefore have impossible consequences. Philosophical history, in its totality, can be interpreted as an attempt to find solutions to this opposition. Many philosophers propose convincing solutions to this antinomy by working on the nuances of concepts, on the complexity of structures of reasoning, on different models of thought. In other words, no philosophy worth its salt falls into the naivety of either position.

La pensée moderne a réalisé un progrès considérable en réduisant l’existant à la série des apparitions qui le manifestent. On visait par là à supprimer un certain nombre de dualismes qui embarrassaient la philosophie et à les remplacer par le monisme du phénomène. Y a t-on réussi ? Il est certain qu’on s’est débarrassé en premier lieu de ce dualisme qui oppose dans l’existant l’intérieur à l’extérieur. sartre beginning of etre et néant It is also important to underline that the formulation of the problem proposed here would have no meaning for some philosophical traditions based on the idea of going beyond the opposition of thinking and Being. For example, the 20th century’s phenomenological approach. However, this problem remains open, and it is renewed today—for many reasons, this will be identified later in this text—giving rise to other perspectives and modes of reasoning: it continuously appears necessary to readdress this opposition and to propose new solutions. This is owing to the very nature of the philosophical gesture, which consists in proposing new structures of thought and inferring logical pathways in order to overcome paradoxes and to (re)interpret the world. This need is justified by the fact that thought always corresponds to the material conditions of its production. These conditions are simultaneously technical, historical, political, social and economic… They are the reasons why it still makes sense to philosophize even after 2,600 years of philosophy. They are some of the reasons determining the necessity of metaontology, a concept which aims to propose a new solution to this old problem.

The problem of multiplicity

As explained, there are two ahistorical reasons justifying the need for metaontology; the question “why is there something?” has a corollary: why are there things, that is, several things? This is the problem of multiplicity. It can be expressed in a very simple way: multiplicity seems to be impossible for many reasons and, despite this impossibility, it seems to be—or to exist. To be more precise: multiplicity seems incompatible with Being. It is impossible to state that there are many things; and yet, it seems that there are many things. There are many things, but the multiplicity to which “many” refers cannot be, thus it is nothing but an illusion.

This problem is deeply linked with the possibility of thinking around difference and otherness and with building theoretically consistent approaches to political and sociological problems like relationships between people, genders, species, etc. One of the main goals of metaontology is to find a solution to this paradox: metaontology aspires to an ontology of multiplicity.

This text will start by identifying four main reasons that demonstrate the impossibility of multiplicity, in order to better understand the problem that metaontology aims to solve. There is, respectively, a logical, an etiological, an epistemological and an ethical reason, and each undermines the possibility of multiplicity.

The logical impossibility of multiplicity

What is your meaning, Zeno? Do you maintain that if being is many, it must be both like and unlike, and that this is impossible, for neither can the like be unlike, nor the unlike like–is that your position? (Plato 2008, 127e. See annotation)12 First of all, multiplicity is impossible from a formal, logical point of view. This impossibility can be expressed as a formulation of the problem of difference and can be summarized as follows:

- There are 2 things: A and B

- This means that A is and B is

- But this also means that A is not B.

- This means that, at the same time, A is and is not; this is impossible.

This formulation is related to two fundamental principles of logic: the principle of non-contradiction and the principle of identity. According to the first one, two contradictory propositions cannot be true: A cannot be and not be. Formally ¬(p ∧ ¬p). According to the second, each thing is identical to itself, and thus A is A.

A possible objection to this formulation is that it confuses two different uses of the verb “to be”. In fact, in the first and in the second sentence (“There are 2 things” and “A is and B is”), the verb “to be” is used to signify the existence of a thing. Is means that A exists. In the third sentence, the negative form of the verb “to be” is used to signify “to be different”: “A is not B” means that A is different from B and not that A is not, meaning that it does not exist.

Sic ergo patet quod prima pluralitatis vel divisionis ratio sive principium est ex negatione et affirmatione, ut talis ordo originis pluralitatis intelligatur, quod primo sint intelligenda ens et non ens, ex quibus ipsa prima divisa constituuntur, ac per hoc plura. Unde sicut post ens, in quantum est indivisum, statim invenitur unum, ita post divisionem entis et non entis statim invenitur pluralitas priorum simplicium. Hanc autem pluralitatem consequitur ratio diversitatis, secundum quod manet in ea suae causae virtus, scilicet oppositionis entis et non entis. Ideo enim unum plurium diversum dicitur alteri comparatum, quia non est illud. [Aquinas (1959), pars 2 q. 4 a. 1 co. 3 annotation13 But the problem is more complex than that: what this paradox shows is that it is impossible to take into account the difference between two things without calling into question a negative structure. This means that difference itself can be conceived only in relation to non-Being. What this formulation shows is not only that the particular things A and B cannot “be” at the same time, it shows that difference is nothing and thus there is no difference. Multiplicity can only be based on difference, but difference is non-Being; it is nothingness.

Another formulation of the logical reason is linguistic: the only way to express multiplicity is to reduce it to a unity with a name. Starting from the name “multiplicity”, it is impossible to express plurality without using a unique notion or concept. Even in the first formulation, it is a matter of 2 “things”, which means that the number two is subordinated to a unity, the concept of a “thing”, which merges with the plurality and reduces it to a unity. This argument should be taken very seriously, especially in the context of a philosophical text. The logic argument means that if a philosophical text aims to develop an ontological approach to multiplicity, it shall question the principle of non-contradiction and of language itself.

The etiological impossibility of multiplicity

εἰ δὴ ἀνάγκη πᾶν τὸ κινούμενον ὑπό τινός τε κινεῖσθαι, καὶ ἢ ὑπὸ κινουμένου ὑπ’ ἄλλου ἢ μή, καὶ εἰ μὲν ὑπ’ ἄλλου [κινουμένου], ἀνάγκη τι εἶναι κινοῦν ὃ οὐχ ὑπ’ ἄλλου πρῶτον, εἰ δὲ τοιοῦτο τὸ πρῶτον, οὐκ ἀνάγκη θάτερον (ἀδύνατον γὰρ εἰς ἄπειρον ἰέναι τὸ κινοῦν καὶ κινούμενον ὑπ’ ἄλλου αὐτό· τῶν γὰρ ἀπείρων οὐκ ἔστιν οὐδὲν πρῶτον)—εἰ οὖν ἅπαν μὲν τὸ κινούμενον ὑπό τινος κινεῖται, τὸ δὲ πρῶτον κινοῦν κινεῖται μέν, οὐχ ὑπ’ ἄλλου δέ, ἀνάγκη αὐτὸ ὑφ’ αὑτοῦ κινεῖσθαι.(Aristoteles 1831 Phys. VIII, 5 see annotation)14 The second group of reasons denying the possibility of multiplicity can be defined as etiological. The argument on which these reasons are based relates to the impossibility of infinite regress and the subsequent necessity of a first cause.

Secunda via est ex ratione causae efficientis. Invenimus enim in istis sensibilibus esse ordinem causarum efficientium, nec tamen invenitur, nec est possibile, quod aliquid sit causa efficiens sui ipsius; quia sic esset prius seipso, quod est impossibile. Non autem est possibile quod in causis efficientibus procedatur in infinitum. Quia in omnibus causis efficientibus ordinatis, primum est causa medii, et medium est causa ultimi, sive media sint plura sive unum tantum, remota autem causa, removetur effectus, ergo, si non fuerit primum in causis efficientibus, non erit ultimum nec medium. Sed si procedatur in infinitum in causis efficientibus, non erit prima causa efficiens, et sic non erit nec effectus ultimus, nec causae efficientes mediae, quod patet esse falsum. Ergo est necesse ponere aliquam causam efficientem primam, quam omnes Deum nominant. (Aquinas 1888 Pars 1, questio 2, art 3. See annotation)15 This argument can be expressed as follows:

- Everything has a cause

- A cause must have a cause

- It is impossible to regress to infinity

- It is necessary that a first cause exists that has no causes

εἰ οὖν ὅπερ ἄν τις ἢ εἴπῃ ἢ νοήσῃ τὸ ὄν ἐστι, πάντων εἷς ἔσται λόγος ὁ τοῦ ὄντος, οὐδὲν γὰρ ἔστιν ἢ ἔσται πάρεξ(Simplicius 1882, 86, annotation)16

When there are several things, these things should have one or some causes. Each cause will have a cause and, in the end, there will be a reason justifying these causes; there will be a final cause. Multiplicity itself must have one cause.

Another way of framing this argument is ontological: everything which is can be understood in the horizon of Being. This formulation is based on the possibility of separating Being from the world, the ontological difference which has been put in parentheses above. According to this idea, Being is not all that is, but it is the reason or the principle for which everything that is, is. Being is thus separated from things that are, i.e. beings. But this separation only strengthens the necessity of reducing everything to unity: if there are many things, these things can be reduced to one single, first principle: Being. In this way, Being can be understood as the one principle that reduces everything to a single unity: in order to be, the many should have one—and only one—principle in common: one must be; otherwise, the multiple will not be. In order to be able to think multiplicity, one should always think it as second to something which precedes it: the unity of Being. Multiplicity is perhaps possible, but always as something issued by unity. Multiplicity can, therefore, never be originary, as it is always derivative.

37. Et comme tout ce détail n’enveloppe que d’autres contingents antérieurs ou plus détaillés, dont chacun a encore besoin d’une analyse semblable pour en rendre raison, on n’en est pas plus avancé, et il faut que la raison suffisante ou dernière soit hors de la suite ou séries de ce détail des contingences, quelque infini qu’il pourrait être.

38. Et c’est ainsi que la dernière raison des choses doit être dans une substance nécessaire, dans laquelle le détail des changements ne soit qu’éminemment, comme dans la source, et c’est ce que nous appelons Dieu. (Leibniz 2008 see annotation)17 In order to have an original multiplicity, one should have a multiple Being, which seems impossible and illogical. This is why metaontology tries to define an originary multiple Being, challenging logic itself—this challenge will be addressed in the middle of chapter 4.

The epistemological impossibility of multiplicity

Le Moi est identique jusque dans ses altérations. Il se les représente et les pense. L’identité universelle où l’hétérogène peut être embrassé, à l’ossature d’un sujet, de la première personne. Pensée universelle, est un “je pense”. (Lévinas 2009, 25)18 The third reason is epistemological: knowledge implies the reduction of each multiplicity to unity. Multiplicity is known by some_one_. This is why metaphysics seems impossible as a form of knowledge. Metaphysics desires to address something that surpasses discourse itself, which seems logically impossible.

I term all transcendental ideas, in so far as they relate to the absolute totality in the synthesis of phenomena, cosmical conceptions; partly on account of this unconditioned totality, on which the conception of the world-whole is based—a conception, which is itself an idea—partly because they relate solely to the synthesis of phenomena—the empirical synthesis; while, on the other hand, the absolute totality in the synthesis of the conditions of all possible things gives rise to an ideal of pure reason, which is quite distinct from the cosmical conception, although it stands in relation with it. Hence, as the paralogisms of pure reason laid the foundation for a dialectical psychology, the antinomy of pure reason will present us with the transcendental principles of a pretended pure (rational) cosmology—not, however, to declare it valid and to appropriate it, but—as the very term of a conflict of reason sufficiently indicates, to present it as an idea which cannot be reconciled with phenomena and experience. See annotation

This argument is deeply entwined with the relationship between Being and thinking: if, as it seems necessary, it is impossible to separate Being and thinking without being dogmatic, this means that the only way to speak about the world is from the point of view of a subject who thinks the world. But this implies that the multiplicity of the world is always reduced to the unity of a subject who thinks it. This is why the very desire of metaphysics—which is to develop a discourse about something which goes beyond what a subject can think and perceive—is impossible.

This argument makes clear, once again, the relationship between the possibility of multiplicity and the possibility of otherness. Saying that multiplicity is impossible is the same as stating that otherness is impossible: everything is necessarily reduced to the unity of the I, which is the subject of an “I think”.

The ethical impossibility of multiplicity

Εἰ γὰρ αὐτὸς τὸ ἀγαθόν, τί ἔδει ὁρᾶν ἢ ἐνεργεῖν ὅλως; Τὰ μὲν γὰρ ἄλλα περὶ τὸ ἀγαθὸν καὶ διὰ τὸ ἀγαθὸν ἔχει τὴν ἐνέργειαν, τὸ δὲ ἀγαθὸν οὐδενὸς δεῖται· διὸ οὐδέν ἐστιν αὐτῷ ἢ αὐτό. Φθεγξάμενος οὖν τὸ ἀγαθὸν μηδὲν ἔτι προσνόει· ἐὰν γάρ τι προσθῇς, ᾧ προσέθηκας ὁτιοῦν, ἐνδεὲς ποιήσεις. (Plotinus 1964 III,8,11)19

The fourth argument is ethical. Even if it seems that an argument of this kind should be weaker than the others, this is not true: ethics is probably the field that orients philosophy the most. Even when this is not explicit, discourses and texts cannot ignore ethical principles because these principles always drive them.

The argument can be expressed as follows:

- The Good must be perfect

- Something perfect cannot lack something

- Multiplicity implies a lack, because an element of multiplicity is without the other elements

- The Good must be one

Oportet igitur idem esse unum atque bonum simili ratione concedas; eadem namque substantia est eorum quorum naturaliter non est diuersus effectus.[ III, 21 annotation]20 From an ethical point of view, it is necessary to claim that the Good is originary and ontologically first, compared to Evil. Thus, the origin must be the One and multiplicity can only be a derivative of the One.

Metaontology’s ambition is directly proportional to the strength of these arguments. In order to be able to develop an ontology of multiplicity, metaontology should find a solution to these four arguments and thus:

L’ensemble de ce travail tend à montrer une relation avec l’Autre tranchant non seulement sur la lo g ique de la contradiction où l’autre de A est le non-A, négation de A, mais aussi sur la logique dialectique où le M ême participe dialectiquement de l’Autre et se concilie avec lui dans l’Unité du système.(Lévinas 2009, 161)21 1. Metaontology must propose a new logic which allows contextualization of the validity of the principle of non-contradiction. This will be the goal of chapter 4 2. Metaontology must propose an understanding of Being which allows an originary multiplicity. This implies a change to the very concept of Being in order to avoid the prospect of Being as a final, homogeneous horizon on which each multiplicity is destined to be reduced. This will also be addressed in chapter 4 3. Metaontology must propose a new conception of thinking in order to avoid the epistemological reduction of everything to an “I think”. This will be the goal of chapters 2 and 3 4. Metaontology must propose a new basis for ethics which allows for a multiple Good. This will be the goal of chapter 6.

Historical reason

Idee uniformi nate appo intieri popoli tra essoloro non conosciuti,debbon’avere un motivo comune di vero. (Vico 1999, 144 see annotation)22 This chapter started by presenting what has been defined as the “ahistorical” reasons justifying metaontology. It is worth asking if such reasons can even exist. It is clear that all the arguments proposed above are actually historical. They are all situated in a specific context and time. It is easy to identify that some formulations of these arguments are typical of ancient Greek philosophy, while others are the result of the analyses and commentaries of Greek philosophy, which developed during the Middle Ages in the context of scholastic philosophy, that is, as part of a particular approach to ancient texts. Some other formulations are modern and reflect the preoccupations of a specific society, as in English society during the 18th century. What has been presented as “ahistorical” is, in reality, always situated in space and time.

Natura di cose altro non è, che nascimento di esse in certi tempi,e concerte guise;le quali sempre,che sono tali,indi tali,e non altre nascon le cose. (Vico 1999, 147 see annotation)23 The idea of “ahistorical reasons” may thus be considered a fiction produced in order to address some problems. The idea behind the notion of “ahistorical reasons” is that some problems can be envisioned as constants within the whole philosophical history even if they are presented in different ways. But is it really possible to abstract a specific formulation in order to grasp a particular problem? It seems that this fiction is simultaneously useful and dangerous. It is useful because it helps to understand the diachronic continuity of some philosophical issues and to avoid the rhetoric of revolution. It is dangerous because it risks implying that a “problem” can be understood as something ideal or abstract that lies behind—or goes beyond—a particular formulation. Before analyzing what has been called “historical reasons”, it is necessary to consider these two opposing claims. This analysis will clarify that the only way to consider some constants in the history of philosophy is to look at them from a specific historical point of view, which will make them historical too. In other words: ahistorical reasons are historically ahistorical, which means that, in order to understand them, one should clearly define the historical motive for which they seem ahistorical today. Metaontology emerges today because the material, historical and place and space-specific context in which this approach is inscribed produces a particular view on the history of philosophy that transforms many place and space specific formulations into constant abstract problems. What has been presented before is a situated fiction that accounts for specific, inscribed problems and abstracts their particular character in order to produce something which can be considered today as a philosophical constant.

His cognitis quaesivi deinde, quid id fuerit, propter quod Hebraei Dei electi vocati fuerint ? Cum autem vidissem hoc nihil aliud fuisse, quam quod Deus ipsis certam mundi plagam elegerit, ubi secure, et commode vivere possent, hinc didici Leges Mosi a Deo revelatas nihil aliud fuisse, quam jura singularis Hebraeorum imperii, ac proinde easdem praeter hos neminem recipere debuisse ; imo nec hos etiam, nisi stante ipsorum imperio, iisdem teneri. (Spinoza 1670 see annotation)24 Why is this fiction useful? Because enables a deeper understanding of the actual, historical grounds for the emergence of metaontology. A certain kind of discourse should be avoided, that is, a discourse that presents some problems and characterizes contemporary discourse as something completely and absolutely new. This is what can be defined as a “rhetoric of revolution”. The danger of this rhetoric relates to the potential to imagine that some specific, historical facts determine a radical shift; this shift demands an entirely new analysis. Completely new, in this case, risks being interpreted as something “absolutely” new, which means—in etymological terms—something that has no relationship with the rest of the history. It is, on the contrary, crucial to understand that history is always continuous and that the only way to avoid an abstract and idealized discourse on today’s problem is to situate them in the continuity of this history. In other words: the fiction producing ahistorical constants is useful in order to historically situate a discourse.

This is why this fiction is paradoxically dangerous at the same time. If one absolutizes the ahistorical aspect, this fiction risks producing the opposite of the desired effect. This text’s first goal is to present thinking as a very material, specific, inscribed object. Thinking is always something inscribed, as will be addressed in chapter 3. Abstracting this material inscription leads to deforming philosophical approaches, making them say something that they actually do not say. Now, this text tries to let other texts speak for themselves, to avoid reducing them to a single interpretation. This text can be understood as a set of commentaries, glosses circulating today in the interstices of other texts, without trying to replace or substitute them. The plurality of voices must remain; this is the goal, the ambition and the challenge of the metaontological approach.

Thinking otherness today

Comme la guerre moderne, toute guerre se sert déjà d’armes qui se retournent contre celui qui les tient. Elle instaure un ordre à l’égard duquel personne ne peut prendre distance. Rien n’est dès lors extérieur. La guerre ne manifeste pas l’extériorité et l’autre comme autre; elle détruit l’identité du Même. La face de l’être qui se montre dans la guerre, se fixe dans le concept de totalité qui domine la philosophie occidentale. (Lévinas 2009, 6)25

After two world wars, it is impossible to think the problem of multiplicity outside of its political implications. The formal tension between unity and multiplicity—which has been expressed above as an ahistorical constant within philosophical discourse—is summarized in an urgent, concrete formulation: how is it possible for philosophy to avoid violence?

From this point of view, the logical reasons that make multiplicity impossible become philosophical principles to justify violence or, even worse, to explain its necessity. If difference can be expressed by the sentence “A is not B” and it can thus be identified with non-being and nothingness, then, from an ontological point of view, it is necessary to reduce B to A. The verb “to reduce” here acquires a very material, and even horrendous, meaning: reducing means physically destroying. Ontology becomes violent politics.

Incapables de respecter l’Autre dans son être et dans son sens, phénoménologie et ontologie seraient donc des philosophies de la violence. A travers elles, toute la tradition philosophique aurait partie liée, dans son sens et en profondeur, avec l’oppression et le totalitarisme du Même. Vieille amitié occulte entre la lumière et la puis- sance, vieille complicité entre l’objectivité théorique et la possession technico-politique ’ « Si on pouvait posséder, saisir et connaître l’autre, il ne serait pas l’autre. Posséder, connaître, saisir sont des synonymes du pouvoir » (TA, p. 190) (Derrida 1964, 337)26

Formal sentences like A and B are embodied in some concrete formulations involving men, women, communities, social classes, animals. “A is not B” can thus be embodied in sentences like: “a woman is not a man” or “an animal is not a human” or “this community is not my community”, “this social class is not the most powerful social class”. An ontological interpretation of sentences like these implies that the first instances of comparison are defined by their lack: there is a unity, the essence of which is complete and what is different from this essence is less than this unity. “A woman is not a man” means that one can define women based on only the purported “completeness” of man. Women are reduced to men because the full essence is on the side of men and the essence of women depends on that of men. The second term of comparison is not only the unit of measure for the first, but the completion or perfection that the first term cannot embody.

Power seemed to be more than an exchange between subjects or a relation of constant inversion between and subject and an Other; indeed, power appeared to operate in the production of that very binary frame for thinking about gender. I asked, what configuration of power constructs the subject and the Other, that binary relation between “men” and “women,” and the internal stability of those terms? Preface (1990) p. xxviii This violent situation is deeply related to the interpretation of the relationship between Being and thinking, as described above. Based on the relationship between Being and thinking, it is possible to identify 4 different perspectives that enable or undermine the possibility of difference and to define the very meaning of difference in distinct ways. The four interpretations are as follows:

- Being is separate from thinking and human beings can know it. This implies that difference is ontologically and epistemologically impossible.

- Being is separate from thinking and human beings cannot know it. This implies that difference is ontologically impossible but epistemologically possible.

- Being and thinking are inseparable and thinking is universal. This implies that difference is epistemologically and ontologically impossible.

- Being and thinking are inseparable and thinking is not universal. This implies that difference is epistemologically and ontologically possible.

Le sujet traité ici est manifestement dans l’air du temps. On peut en relever les signes: l’orientation de plus en plus accentuée de Heidegger vers une philosophie de la Différence ontologique; l’exercice du structuralisme fondé sur une distribution de carac- tères différentiels dans un espace de coexistence; l’art du roman contemporain qui tourne autour de la différence et de la répéti- tion, non seulement dans sa réflexion la plus abstraite, mais dans ses techniques effectives; la découverte dans toutes sortes de domaines d’une puissance propre de répétition, qui serait aussi bien celle de l’inconscient, du langage, de l’art. Tous ces signes peuvent être mis au compte d’un anti-hégélianisme généralisé: la différence et la répétition ont pris la place de l’identique et du négatif, de l’identité et de la contradiction. (Deleuze 1994, 1)27 There are, therefore, two perspectives in which difference is in some way possible: the second one that allows a weak form of difference (only epistemological) and the fourth one that allows a strong possibility of difference.

It is now necessary to analyze, in detail, each of these perspectives and their consequences.

- Being is separate from thinking and human beings can know it. This is the position which has been defined above as “dogmatic realism”. It affirms that Being is something absolute which is independently from any relation that someone or something can have with it. This position is dogmatic because there seems to be no rational way of demonstrating it, for the simple reason that the only fact of affirming the absolute character of Being involves creating a relationship with it: this is why this idea is dogmatic. But from the point of view of difference, this position is untenable not only because it is dogmatic, but especially because it strongly refuses any form of difference. In fact, if Being is separate from thinking and human beings can know it, it is necessary that:

- Being is one

- essence is one

- difference is defined by lack

- difference is thus identified with nothingness

L’Autre n’est pas la négation du Même comme le voudrait Hegel. Le fait fondamental de la scission ontologique en Même et en Autre, est un rapport non allergique du Même avec l’Autre. La transcendance ou la bonté se produit comme plura lisme. Le pluralisme de l’être ne se produit pas comme une multiplicité d’une constellation étalée devant un regard possible, car ainsi déjà, elle se totaliserait, se ressouderait en entité. Le pluralisme s’accomplit dans la bonté allant de moi à l’autre où l’autre, comme absolument autre, peut seulement se produire sans qu’une prétendue vue latérale sur ce mouvement ait un quelconque droit d’en saisir une vérité supérieure à celle qui se produit dans la bonté même. On n’entre pas dans cette société pluraliste sans touj ours, par la parole (dans laquelle la bonté se produit) rester en dehors; mais on n’en sort pas pour se voir seulement dedans. L’unité de la pluralité c’est la paix et non pas la cohérence d’éléments constituant la pluralité.(Lévinas 2009, 340–41)28 This is true from an ontological point of view but, given that Being is knowable, knowledge must also refuse difference. Therefore, difference is also impossible from an epistemological point of view. The true knowledge is the knowledge of unity and any difference is nothing but an illusion.

- Being is separate from thinking and human beings cannot know it. This position is a weak form of what has been called “correlationism”. In order to avoid dogmatism, it stipulates that it is impossible to know Being. This means that, from an ontological point of view, difference is impossible (for the same reason as the previous point), but it is possible that there are many ways of thinking. Plurality can thus exist in the way someone or something sees or thinks the world. Being is one, but it can be seen in different ways, from different points of view. The argument goes like this:

- Being is one

- essence is one, but human beings cannot know it

- there are different points of view on the world

- difference depends on points of view for human beings

- but there is actually an essence and thus, from an ontological point of view, difference is defined by lack, as in the first point.

Un tel type de métaphysique peut sélectionner diverses instances de la subjectivité, mais elle se caractérisera toujours par le fait qu’un terme intellectif, conscientlel, ou vital sera ainsi hypostasié: la représentation dans la monade leibnizienne; le sujet-objet objectif, c’est-à-dire la nature de Schelling; l’Esprit hégélien; la Volonté de Schopenhauer; la volonté de puissance (ou les volontés de puissance) de Nietzsche; la perception chargée de mémoire de Bergson; la Vie de Deleuze. etc. Même si les hypostases vitalistes du Corrélat (Nietzsche, Deleuze) sont volontiers identifiées à des critiques du «sujet», voire de la «métaphysique», elles ont en commun avec l’idéalisme spéculatif la même double décision qui leur garantit à elles aussi de ne pas être confondues avec un réalisme naïf, ou avec une variante de l’idéalisme transcendantal: 1. rien ne saurait être qui ne soit pas un certain type de rapport-au-monde (l’atome épicurien, sans intelligence, ni volonté, ni vie, est donc impossible); 2. la proposition précédente doit être entendue en un sens absolu, et non pas relativement à notre connaissance.(Meillassoux 2012, 51)29 This perspective allows a weak form of difference: there is no difference from an ontological point of view and, if one could know Being, one would see that it is one. But because it is impossible for knowledge to grasp Being, it is possible to have many—always imperfect—views of and on it. Multiplicity can exist from an epistemological point of view because of the weakness of knowledge. This perspective is less violent than the first one because it avoids the fact that someone or something can decide where the real and the true unity stand. But difference is again defined as a lack. This perspective has another problem: how is it actually possible to state that Being is separate from thinking if no one can know it? This statement seems to be as dogmatic as the first perspective. Also, for difference to be possible, it is necessary for thinking to be multiple and thus non-universal; this has some complex consequences, as observable in the fourth point.

Being and thinking are inseparable and thinking is universal. If Being and thinking are inseparable, this inseparability must be understood as identity. Otherwise, this perspective could be assimilated to perspective 2. Being and thinking are inseparable because they are the same thing. Ontology and epistemology are thus merged together. The possibility of multiplicity will therefore depend on how thinking is structured. If thinking is universal, this means that it does not take many forms: it is impossible to have a plurality of points of view because, if they exist, they can be reduced to a unique, final, correct point of view. The identity of thinking and Being has thus the same consequences as perspective 1: it determines an epistemological impossibility of difference, which also corresponds to an ontological impossibility.

car la raison corrélationnelle, en se découvrant marquée d’une limite irrémédiable, a légitimé d’elle-même tous les discours qui prétendent accéder à un absolu, sous la seule condition que rien dans ces discours ne ressemble à une justification rationnelle de leur validité. Loin d’abolir la valeur de l’absolu., ce que l’on nomme volontiers, aujourd’hui, la «fin des absolus» consiste au contraire en une licence étonnante accordée à ceux-ci: les philosophes semblent ne plus en exiger qu’une seule chose, c’est que rien ne demeure en eux qui se revendique de la rationalité. (Meillassoux 2012, 61)30Being and thinking are inseparable and thinking is not universal. This perspective is the only one allowing a strong possibility of difference. If Being is identical to thinking—which is another way of stating that there is nothing but thinking—and thinking is multiple, there is something like an originary difference, which is irreducible to any unity. This perspective seems to solve the problem of difference, but the price to pay is very high for two reasons. The first one relates to the fact that an originary, multiple thinking implies the impossibility of any form of rationality and understanding, a situation that also affects perspective 3. From an epistemological point of view there is no longer a principle of non-contradiction or a principle of identity because different forms of thinking are on the same level. A and not-A could be simultaneously true because there is no unique, universal point of view. But what is even more problematic is the fact that this situation is also true from an ontological perspective if Being and thinking are inseparable (which is not the case for perspective 3). If perspective 3 implies the impossibility of rationality and understanding, perspective 4 seems to imply the impossibility of any reality.

The ambition of metaontology is to embrace perspective 4 without losing the possibility of rationality and reality. This is why metaontology aims to produce an ontological—as opposed to a purely epistemological—discourse that is capable of thinking otherness and difference without reducing it to a unity. This means that metaontology should think of difference without reducing it to the thinking of metaontology itself. Metaontology will need to solve the paradox that, if otherness and difference are thinkable, then they are no more other and different; if they are not thinkable, it is impossible to speak about them. In other words, metaontology aims to think an ontologically and an epistemologically originary multiplicity and to develop, from this multiplicity, the possibility of a multiple reality.

Where is the real today?

Le fanatisme contemporain ne saurait donc être tenu simplement pour la résurgence d’un archaïsme violemment opposé aux acquis de la raison critique occidentale, car il est au contraire l’effet de la rationalité critique, et cela en tant même - soulignons-le - que cette rationalité fut effectivement émancipatrice - fut effectivement, et heureusement, destructrice du dogmatisme.(Meillassoux 2012, 67)31 The 20th century’s philosophical struggle has often tried to make difference possible without reducing it to rationality and to reality. The strongest the possibility of difference—as in perspective 4—, the weakest the rationality and reality. As shown above, there are two parallel strategies that must combine in order to make difference possible: the first strategy involves avoiding the separation of thinking and Being; the second involves deny the possibility of universal thinking.

In fact, as will quickly become clear, to deploy the diversity of felicity conditions it would do no good to settle for saying that it is simply a matter of different “language games.” Were we to do so, our generosity would actually be a cover for extreme stinginess, since it is to language, but still not to being, that we would be entrusting the task of accounting for diversity. Being would continue to be expressed in a single, unique way, or at least it would continue to be interrogated according to a single mode—or, to use the technical term, according to a single category . Whatever anyone might do, there would still be only one mode of existence —even if “manners of speaking”—which are not very costly, from the standpoint of ordinary good sense—were allowed to proliferate.(Latour 2013, 20) The first point seems necessary for at least two reasons. First of all, it is impossible to claim an independence of Being and thinking without falling into dogmatic realism; it is impossible to talk about something with which there is no relationship. The very fact of “talking” about something is already a relationship. Secondly, if Being is separate from thinking, this means that any thinkable plurality will be ontologically reduced to the unity of Being. It is thus necessary to deny the separation of Being and thinking. This has a first important consequence: if Being and thinking are not separate, then thinking cannot be interpreted as a representation of Being. From a perspective like the first one, there is, on one hand, Being and, on the other hand, thinking which represents Being. There is a cow—which is, regardless of any form of thinking—and then there is the fact of thinking a cow. The thought cow is a representation of the cow itself. But if there is no longer a separation between Being and thinking, this dual relationship no longer functions; thinking is no longer thinking something. The mimetic relationship is broken and there is just the thought-being. This thought-being does not refer to something else: the thought cow is not a representation of the cow. There is no referent to thinking. This means that there is no way of deciding whether the thought cow is the result of a correct form of thinking. Therefore, if there are two thought cows, both of them are ontologically on the same level of legitimacy.

The second strategy consists in denying the possibility of a universal form of thinking. If thinking is universal, there is only one thought cow and one therefore faces the same problem as if Being and thinking were separated: every multiplicity is eventually reduced to a universal unity—in this case, not one of Being, but that of thinking.

After these two strategies are actualized, there is no more a stand-alone Being—something like a cow—and there is no way to compare two or more different thought cows.

On 8 November 2016, as the writing of this book neared com- pletion, the voters of the United States elected the scandal- ridden businessman and reality television star Donald J. Trump as their next President.[…] As usual, one of the most contrarian pos- itions was taken by the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek, who persisted in his pre- election claim that a Clinton victory would simply lead to more neoliberal mediocrity, while a win for the aspiring strongman Trump would at least serve to galvanize new and surprising political coalitions. 1 A more common reaction, however, was to condemn Trump’s victory as the sign of a world that no longer has any respect for truth. Subtly leading the charge was no less an authority than the Oxford English Dictionary, which enshrined ‘post-truth’ as its 2016 word of the year, defining the term as ‘relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief’. 2 No one could miss the implied refer- ence to a specific, newly minted American politician. If we believe the OED ’s definition, the best remedy for our supposedly post-truth condition would be ‘objective facts’.(Harman 2018, 3–4.) Post- modernism is retreating, both philosophically and ideologically, not because it missed its goals but, on the contrary, precisely because it hit them all too well. The massive phenomenon— and, I would say, the main cause of the turn—was precisely this full and perverse realization that now seems close to implosion.(Ferraris, De Sanctis, and Harman 2014, 3.) These two strategies seem necessary to allow difference and otherness, but, if they are radicalized, they deny the possibility of rationality and reality. Continental philosophy in the 20th century, in attempting to make difference possible, generated a reaction in the beginning of the 21st century: it seems that the issue no longer relates to allow difference, but to bringing reality back. What is curious is that both the tendency of making difference possible and that of bringing back reality stem from complementary political concerns. War, violence, domination and exploitation seem founded on the idea of unity. Everything can be reduced to a unity: one good, one ethics, one society, one humankind. From this standpoint, it is always possible—and even necessary—to fight and destroy everything which does not correspond with predefined unity. In merging Being and thinking, philosophical discourse during the 20th century stated that these unities, which were grounds for violence, were actually the result of power and not a requirement of “nature”. The notion of “Being is thinking” means, for example, that the essence of human beings is not as it is for an ontological, unchangeable reason; the essence of human beings is a production of discourse and this discourse is driven by power. The same essence can be produced in many different ways. This statement can be used as a starting point to condemn violence. It is impossible to justify the reduction to unity because each unity is the result of power. Ethically, there is no way of basing a reduction to unity on an ontological principle. For example: one cannot state that one race is better than another because it is closer to a predefined essence of human being. One cannot state that women have a particular place in society because of their nature. One cannot say that a particular sexual behaviour is to be condemned because it is not natural. There is no such thing as the essence of human beings or the nature of women or natural sexual behaviour, simply because all these ideas are nothing but the product of a particular power-driven form of thinking. Once again: the same essence can be produced in many different ways.

But is it possible to limit this “many” in order to prevent it becoming “any”? If not, essences can be produced in any way: the world is production and it is impossible to identify boundaries to this production. This is what has been labelled above as a radical constructivist point of view. The political problem is now a different one: how is it possible to avoid some forms of violence which are based on the idea that one can build reality as one likes? If the world can be produced in any way, then all these productions are on the same level of legitimacy. A scientific statement about the mass of the Earth is on the same level as a Flat Earth Theory. A historical statement could be replaced by any other statement. There are no more facts, just discourse, and this discourse has no limits, no boundaries. Violence is no longer founded on the impossibility of difference, but on a difference which is so radical that it makes everything undifferentiated again. A philosophical approach aiming to promote tolerance, in this way, implies the impossibility of objectivity.

Nell’ultimo anno il dibattito filosofico italiano è stato occupato dalla rinata disputa tra realisti e antirealisti. Con una serie di articoli su riviste specialistiche come MicroMega e con una impegnativa campagna condotta sulle pagine dei principali quotidiani italiani, da Repubblica al Corriere della Sera, Maurizio Ferraris ha proposto di riportare al centro della discussione il concetto di “realtà”, a suo dire liquidato nei passati decenni dal postmodernismo e dalla decostruzione, dall’ermeneutica e dal pensiero debole (FERRARIS 2011). Quest’ultimo in particolare viene individuato come responsabile della polverizzazione della realtà, processo dalle imprevedibili conseguenze reazionarie: una volta misconosciuto il valore dei fatti, la molteplicità delle interpretazioni non ha favorito l’emancipazione e la libertà degli individui ma, paradossalmente, ha assecondato il «populismo mediatico» trasformando la realtà in «reality» (FERRARIS, VATTIMO 2011). Mosso dunque da istanze teoretiche ed etiche, il Nuovo Realismointerviene a riabilitare il valore inemendabile dei fatti contro la deriva delle interpretazioni. (Oliva 2012, 53) It is important to underline that this disappearance of reality and objectivity is not claimed or determined directly by philosophical discourse. A close reading of any text of what has been labeled as “post-structuralism” will show that this risk was very clear and that many strategies were deployed in order to avoid it. The tension between the possibility of difference and otherness and the possibility of an objective reality has been at the centre of philosophical discourse since its beginnings and all philosophical texts address it in some way or another. It is true, however, that some 20th century texts, as it has been transferred in less specialized discourses—like mass-media or literature—, seem unable to help with the contemporary feeling that reality becomes less and less graspable.

What is interesting about this situation is that this problem does not concern only—nor mostly—the philosophical field, but society at large. Topics like the relationship between ontology and epistemology, Being and thinking, difference and reality—which were once relegated to very small, specialist communities—become issues of public interest.

But why speak of an inquiry into modes of existence? It is because we have to ask ourselves why rationalism has not been able to define the adventure of modernization in which it has nevertheless, at least in theory, so clearly participated. To explain this failure of theory to grasp practices, we may settle for the charitable fiction proposed above, to be sure, but we shall find ourselves blocked very quickly when we have to invent a new system of coordinates to accommodate the various experiences that the inquiry is going to reveal. For language itself will be deficient here. The issue—and it is a philosophical rather than an anthropological issue—is that language has to be made capable of absorbing the pluralism of values. And this has to be done “for real,” not merely in words. So there is no use hiding the fact that the question of modes of existence has to do with metaphysics or, better, ontology —regional matters, to be sure, since the question concerns only the Moderns and their peregrinations.(Latour 2013, 19 annotation) One particular manifestation of this debate relates to the status of scientific knowledge. If reality is always the production of power, how can one affirm the objectivity and the validity of scientific knowledge? In 21st century western societies, there is a tension between the impact and the presence of scientific discourses—inherited from modernity—and the idea of a power-driven reality.